Activists say they also are growing increasingly impatient with President Joe Biden and his reluctance to demand an end to the Senate’s filibuster rule that establishes a 60-vote threshold to advance most legislation in the chamber. They want Biden to exert pressure on Democratic holdouts on the filibuster to allow a pair of federal voting bills to pass the Senate by a simple majority vote. The bills, activists say, will counteract efforts by Republicans to restrict voting access as former President Donald Trump and his allies persist with false claims of a rigged election.

“This is time for action, not words,” said Fred Wertheimer, president of Democracy 21, an election watchdog group. Biden “has to engage in this fight or he’ll share responsibility for potentially millions of Americans losing the ability to vote in future federal elections.”

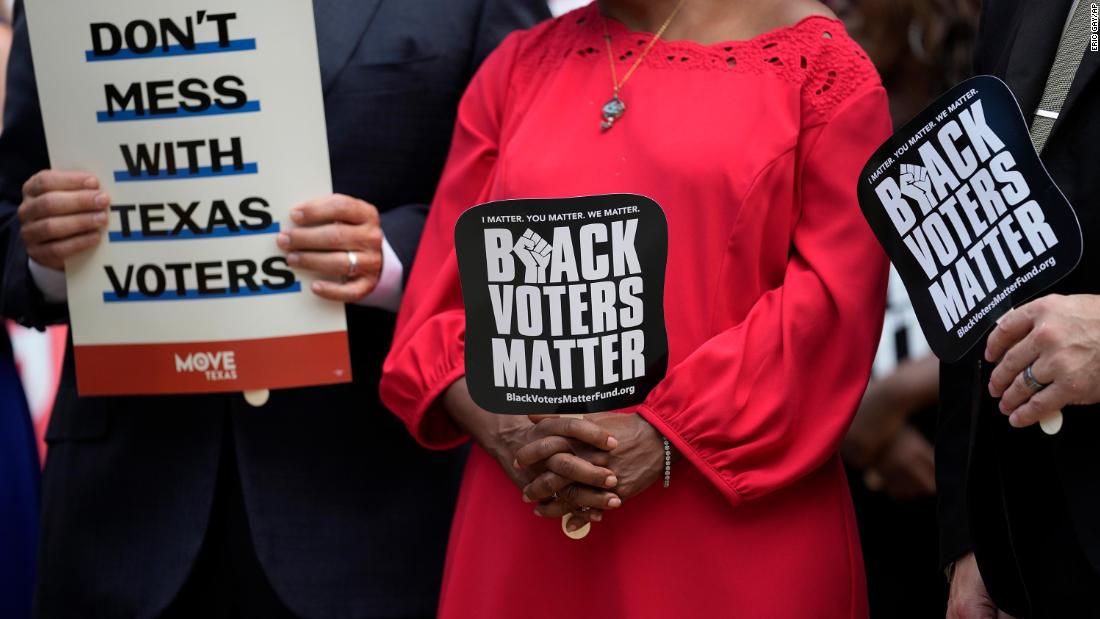

The pressure campaign includes a four-day “Moral March for Democracy” in Texas led by prominent civil rights activist Bishop William Barber, former Texas congressman Beto O’Rourke and others. The march is slated to start Wednesday in Georgetown, Texas, and will end with a rally Saturday at the Texas state Capitol in Austin, imploring Congress to act.

Country legend Willie Nelson plans to join Saturday’s rally, which also will cast a spotlight on efforts by Republicans in the Lone Star state to advance their broad package of voting restrictions. In a dramatic act of civil disobedience, dozens of Democratic state legislators this month fled Texas, denying the GOP-controlled House the quorum needed during a special legislative session to take up election measures.

In Washington, meanwhile, Martin Luther King III and the Rev. Al Sharpton plan to visit Capitol Hill on Wednesday to call on congressional leaders to pass federal voting rights legislation.

And on Thursday, several women’s groups also plan “direct action” in the US Senate, said Melanie Campbell, who oversees the Black Women’s Roundtable. Earlier this month, Campbell was among several demonstrators — including Ohio Democratic Rep. Joyce Beatty, who chairs the Congressional Black Caucus — arrested at a voting rights protest in the Senate Hart Building.

Last week, dozens of organizations, including the NAACP and the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, released a letter, calling for Biden’s “direct engagement and leadership in efforts to secure the passage of these critical voting rights bills.”

White House officials maintain that Biden is committed to federal legislation but say the administration also is working on other fronts to protect ballot access — including Vice President Kamala Harris’ high-profile efforts to elevate the issue — in the face of unified Republican opposition on Capitol Hill.

They note that Biden has signed an executive order, promoting voter registration and access, and that Justice Department has boosted its staff to step up enforcement of voting laws. Last month, the agency sued the battleground state of Georgia over its new voting restrictions.

Biden and Harris “are incensed by the anti-voter laws that are trampling on our constitutional principles and which are based on a dangerous lie that led to one of the darkest days in the history of American Democracy,” Andrew Bates, a White House spokesman, said in a statement to CNN.

“That’s why they are fighting for landmark voting rights legislation that every Democrat has voted to move forward with despite GOP obstruction, and why an all-of-government effort on voting rights was launched by the administration – including the President’s historic executive order, the work the Vice President is leading to mobilize for progress on this issue, and a doubling of the voting rights staff in the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division.”

Time is running out

Voting rights groups, however, warn that time is running out for Congress to jump-start the stalled election legislation — as states gear up for the 2022 midterm elections and prepare to draw maps for new congressional and legislative districts following the 2020 Census.

Democrats are pushing two federal bills: The For the People Act, a broad overhaul of federal elections and ethics laws that would nullify some of the voting restrictions passed by states, and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would restore provisions of the landmark 1965 law gutted by the US Supreme Court in 2013.

The For the People Act also seeks to outlaw partisan gerrymandering.

But both bills face nearly impossible odds in Congress. Republicans, who cast the For the People Act as a partisan, federal overreach into elections, blocked its consideration last month in the Senate, where Democrats have the slimmest possible majority.

And a number of Democrats, including Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Simena of Arizona, have opposed dismantling the filibuster rules to allow their party to advance legislation by a simple majority with Harris casting the tie-breaking vote. Manchin also opposes the sweeping For the People Act and wants a pared-down bill focused narrowly on protecting voting rights and procedures.

The frustration with the White House has been brewing, but activists have grown more vocal, following Biden’s contention at a CNN town hall last week that abandoning the filibuster would throw the “entire Congress into chaos.”

“What I want to do is I’m trying to bring the country together, and I don’t want the debate to only be about whether or not we have a filibuster or exceptions to the filibuster or going back to the way the filibuster had to be used before,” Biden told CNN’s Don Lemon at the town hall in Cincinnati.

“I know he’s a son of the Senate,” Barber said of Biden in an interview with CNN. “But at the moment, he’s got to look at the honest truth: The filibuster has never brought people together.”

Barber, who was arrested alongside the Rev. Jesse Jackson on Monday during a voting rights protest at Sinema’s Phoenix office, has called on Biden to travel to states such as Arizona and West Virginia to pressure recalcitrant lawmakers.

White House officials privately argue that Biden has few options to sway senators such as Manchin, who represents a deep-red state that Biden lost in 2020, even if the president were inclined to abandon the filibuster.

Still, activists are calling on the President to exert as much of his presidential power on voting issues as he is on efforts to pass his signature infrastructure plan. (On Tuesday, Biden huddled with Sinema, at the White House as he worked to keep bipartisan infrastructure negotiations on track. Sinema is the lead Democratic negotiator in the talks.)

“No one is questioning that infrastructure is important, but there isn’t the same sense that he’s staking his personal agenda on this issue,” said Daniel Weiner, deputy director of the election reform program at the liberal-leaning Brennan Center for Justice.

“When presidents want to get something done, they throw their energy into finding a path.”

In all, 18 states have passed 30 new laws restricting voting as of mid-July, according to a tally by the Brennan Center. They range from imposing new voter identification requirements to cast ballots by mail and limits on the use of ballot drop boxes to measures that make it harder to remain on absentee voting lists.

At last week’s town hall, Biden suggested that an energized voter base would not be deterred by the new restrictions, citing 2020 record turnout during the pandemic.

“Look, the American public, you can’t stop them from voting,” he said. “You tried last time. More people voted last time than any time in American history, in the middle of the worst pandemic in American history. More people did.”

“And they showed up,” he added. “They’re going to show up again.”

To help counteract the raft of new restrictions, Harris recently announced that the Democratic National Committee would spend $25 million to help register and educate voters ahead of the 2022 midterms. Officials say the money will help establish a voter protection team that will help reach people who might be affected by the new voting restrictions.

But voting rights activists say it’s hard for their organizing to overcome all the new hurdles erected by state laws.

New provisions in Georgia, for instance, ban third-party groups from providing snacks or water to people waiting to cast their ballots — so-called “line warming” that activists used last year to encourage people to remain in hours-long lines at crowded polling places. Critics said the practice allowed partisan players to engage in electioneering near polling places.

And other states, including Florida and Iowa, have restricted the ability of outside groups to help voters return absentee ballots.

“You are asking us to work miracles,” said Cliff Albright, the co-founder of Georgia-based voting rights group Black Voters Matters. “It’s really insulting.”

Nsé Ufot, who runs the New Georgia Project, said Democrats in Washington need to wield their power while they have it.

“I’m growing increasingly frustrated with not only the administration’s response, but the entire Democratic establishment,” she said. “…When you continue to tell us that this is a priority for your administration and a priority for your party, I need to see evidence of that.”