Standing in the cold, the hulking planes rumbling in the background, Biden knew who to call.

“Mr. Secretary,” he told Colin Powell over a satellite phone, “they said you kicked me off this plane.”

Powell had not, in fact, kicked Biden or anyone off the plane. Then serving as President George W. Bush’s secretary of state, Powell had an idea who might have.

“Rumsfeld!” he declared, uttering the name of President George W. Bush’s first defense secretary. “Goddammit!”

After a fiery call to US Central Command, Powell had secured seats for Biden and his team to leave.

The scene from Bagram Air Base, which Biden recounted in his memoir “Promises To Keep,” came months after the American invasion of Afghanistan. Then serving as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Biden was on a fact-finding mission for a conflict he’d begun to question.

Powell, who died Monday at 84, had already found himself enmeshed in a foreign policy battle with fellow Cabinet members for Bush’s ear. The disputes would intensify over the coming years as colleagues like Vice President Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld agitated for invading Iraq — a decision Powell later said he had reservations about, even as he made the case for it in public.

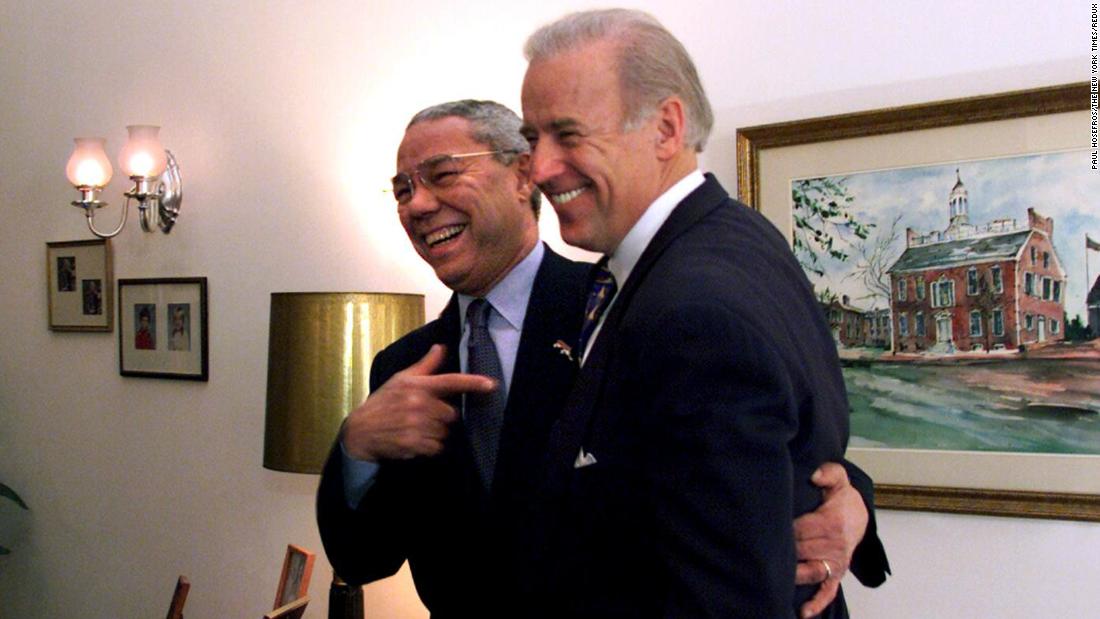

Biden often found himself on Powell’s side. Stalking the hallways of power together for decades, the two men represented an era of bipartisan policy agreement that now seems antiquated and even, in the case of the Iraq War, ill-advised. In his final year, Powell seemed as horrified as Biden at the state of the Republican Party, which he said had allowed conditions to foment that led to the violence of the January 6 insurrection at the US Capitol.

“I became friends with Colin Powell, who we just lost,” Biden said Monday afternoon on the White House South Lawn, where he was speaking at at event honoring teachers. “He’s not only a dear friend and a patriot, one of our great military leaders and a man of overwhelming decency. But this is a guy born the son of immigrants in New York City, raised in Harlem in the South Bronx. A graduate from the City College of New York, and he rose to the highest ranks not only in the military, but also in areas of foreign policy and statecraft.”

Earlier in the day, Biden had ordered flags flown at half-staff to honor the life of his friend.

“Over our many years working together — even in disagreement — Colin was always someone who gave you his best and treated you with respect,” Biden wrote in a statement.

“From his front-seat view of history, advising presidents and shaping our nation’s policies, Colin led with his personal commitment to the democratic values that make our country strong,” Biden added. “Time and again, he put country before self, before party, before all else — in uniform and out — and it earned him the universal respect of the American people.”

Bound by concepts of civility, experience and working-class values — and a love of vintage muscle cars — Biden and Powell experienced alongside one another some of the last century’s final foreign policy moments, and this century’s first ones. For most of those decades they were in opposing camps, Biden a Democrat and Powell a Republican.

They met in the middle — and, in 2016, on a racetrack with Jay Leno, where they revved their Corvettes and exchanged some light trash talk.

“Where were you?” Powell called out to Biden. “I kept looking in the mirror and I didn’t see you.”

Biden viewed Powell through the lens of his decades-long military career, during which he claimed political independence. He regarded him as a steadying influence on a string of US presidents and saw in his worldview a foreign policy doctrine that, at times, matched his own — rooted in clear objectives and support from the American people.

“Above all, Colin was my friend,” Biden wrote in his statement. “Easy to share a laugh with. A trusted confidant in good and hard times. He could drive his Corvette Stingray like nobody’s business—something I learned firsthand on the race track when I was Vice President. And I am forever grateful for his support of my candidacy for president and for our shared battle for the soul of the nation. I will miss being able to call on his wisdom in the future.”

Growing close during the Bush years

Biden came to view Powell as a steadying — if often crowded-out — voice in Bush’s administration. He repeatedly appeared before Biden’s foreign relations panel, including during Powell’s confirmation hearings when Biden voiced his wonder at Powell’s performance.

“I have not seen any notes slipped to you and there has not been a binder in front of you, and this has been a tour de force on your part, and you should be complimented publicly for that,” Biden said before the committee voted unanimously to advance his nomination.

In Powell’s early days serving as Bush’s secretary of state — a return to public life after a decades-long military career that gained him widespread trust among the American people, according to polls — Biden often encountered him in the Senate or at the White House.

When Biden was summoned to the White House to consult with Bush ahead of his first trip to Europe, he arrived to the Oval Office just as Powell was leaving. Bush called out to his top diplomat so Biden could hear.

“Colin!” Bush said, cackling. “Remember to pack clean underwear.”

“See what I have to put up with, Mr. Chairman?” Powell joked as he passed Biden on his way out.

The ensuing years would test Powell’s influence in the administration, a dynamic Biden watched closely from his perch on Capitol Hill. As hawks like Cheney and Rumsfeld advocated for war in Iraq, Biden was confident in Powell’s ability to offer a dissenting voice — even as he questioned whether the secretary of state was being kept in the loop.

“Powell and the State Department were as much in the dark as I had been on that sightless night on the tarmac in Bagram,” Biden wrote in his book. “As I look back on it, I have come to believe that no matter how close Powell was to the president, it seemed George W. Bush had a way of keeping his foreign policy hidden from his own secretary of state.”

When Biden expressed reservations about invading Iraq directly to Powell, he often received an auspicious response: “Call the president,” Powell would tell Biden. “Tell him what you just told me.”

Mutual regret over Iraq war

In the end, both Powell and Biden took steps they later regretted in the lead-up to the Iraq War. Powell’s lengthy speech at the United Nations laying out the case for a US-led war to disarm Saddam Hussein helped persuade many Americans — including Biden — to get behind the effort; later, Powell said the address would forever be a “blot” on his record.

Biden voted to authorize the use of military force in Iraq in 2003 but had come to view the vote as a mistake by 2005. Fifteen years after, he was still forced to answer for it — sometimes in misleading ways — during his run for president last year.

Catching up years after the invasion of Iraq at a birthday party, Powell and Biden began to reminisce about his time in the Bush White House. Standing on a back porch as other partygoers went inside, Powell sounded flummoxed by the experience.

“I think I have him. I think he agrees. And then he goes the opposite way,” Powell told Biden. “I don’t know what’s wrong with him.”

Biden took a more jaundiced view.

“I remember that night thinking how Powell was kidding himself about Bush, like he still had to rationalize to himself that he’d been outmaneuvered in a political game by these two shrewd old hands; he still wouldn’t recognize that President Bush had simply made the wrong decisions,” he wrote in his book.

‘We need people who will speak the truth’

Still, the mutual respect between the two men persisted. By the time Biden was making his third run for president, Powell had completed a break with the GOP that began in 2008, when he endorsed Barack Obama — and by extension Biden, his running mate — in the final weeks of a heated presidential election.

Powell’s decision to endorse Obama over his friend and fellow Vietnam War veteran Sen. John McCain was a turning point; his backing eased concerns among some moderate voters that Obama lacked sufficient foreign policy experience, the same concerns Biden’s selection as a running mate were meant to alleviate.

The endorsement launched a private relationship between Obama and Powell — the first Black president and the first Black secretary of state — that lasted Obama’s presidency. Obama, along with other top administration officials, consulted Powell on the war in Afghanistan and other foreign policy matters. Powell, still a moderate Republican, offered light criticism of how the young administration was focusing its energies.

“He should have focused on the economy … to the exclusion of most everything else domestically,” Powell told CNN’s Larry King in 2010. “When you’re starting out as a president, you have to figure out (what) is most important.”

Yet in 2012, Powell endorsed Obama again, this time over Mitt Romney. He said at the time that he believed it continuity — and he wasn’t sure where Romney stood on foreign policy.

“I signed on for a long patrol with President Obama, and I don’t think this is the time to make such a sudden change,” he said.

He would never again endorse a Republican presidential candidate, backing Hillary Clinton in 2016 and finally Biden last year. The prospect of another four years of Trump — the same motivation that drove Biden into the race — had brought the men together again.

“I certainly cannot in any way support President Trump this year,” Powell told CNN’s Jake Tapper, adding he is “very close to Joe Biden on a social matter and on a political matter.”

“I worked with him for 35, 40 years,” he said, “and he is now the candidate, and I will be voting for him.”

Speaking at Biden’s own virtual nominating convention, Powell argued his longtime Washington colleague was the best candidate to win over moderate Republicans.

“Joe Biden will be a president we will all be proud to salute,” Powell added. “With Joe Biden in the White House, you will never doubt that he will stand with our friends and stand up to our adversaries — never the other way around,” Powell said in a video released by the Democratic National Convention Committee ahead of the second night of convention programming.

Five months later, after would-be insurrectionists stormed the US Capitol where Biden’s election victory was being certified, Powell had made his final break with the Republican Party.

“You know I’m not a fellow of anything right now,” Powell said on CNN’s “Fareed Zakaria GPS.”

“I’m just a citizen who has voted Republican, voted Democrat, throughout my entire career, and right now I’m just watching my country and not concerned with parties.”

“We need people that will speak the truth,” Powell added.